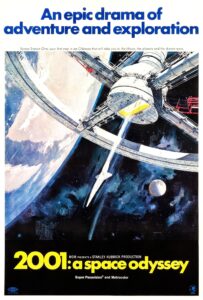

Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey can be considered the Citizen Kane of science fiction, in that it features a revolutionary visual style (a style matched with a bit of bravado, as if the director were saying “Look what I can do!”) that had an outsized influence on the movies that followed it. And, like Kane, it was controversial when it came out, and remains so to this day, with many people considering it arty and pretentious.

There’s no question that 2001 can be a difficult film to watch. It moves at a deliberate pace, not willing to speed up to satisfy those with short attention spans. The long and seemingly endless shots of spacecraft in motion can try the patience of the most ardent fan. When the movie was released in 1968, such sequences were intended to instill a sense of awe in the audience, giving them glimpses of space and future technology far beyond what had been seen in earlier sf films — though, even then, many viewers got restless waiting for something to happen. (Supposedly, Rock Hudson walked out of the premiere screening, muttering “What is this bullshit?”) In this day and age, when any hack moviemaker has access to technology far beyond that available to Kubrick and special effects director Douglas Trumbull, a modern viewer might well wonder what the big deal is. And where are the damned aliens already?

There’s no question that 2001 can be a difficult film to watch. It moves at a deliberate pace, not willing to speed up to satisfy those with short attention spans. The long and seemingly endless shots of spacecraft in motion can try the patience of the most ardent fan. When the movie was released in 1968, such sequences were intended to instill a sense of awe in the audience, giving them glimpses of space and future technology far beyond what had been seen in earlier sf films — though, even then, many viewers got restless waiting for something to happen. (Supposedly, Rock Hudson walked out of the premiere screening, muttering “What is this bullshit?”) In this day and age, when any hack moviemaker has access to technology far beyond that available to Kubrick and special effects director Douglas Trumbull, a modern viewer might well wonder what the big deal is. And where are the damned aliens already?

Obviously, given the fact that I’m including 2001 in my Ten Best list, I think the movie is still a big deal. I first saw it on TV when I was about fifteen. Catching the broadcast a small television, broken up by ads, is not of course the ideal way of seeing any movie, let alone 2001, which depends on its visuals for much of its power. Certainly, I didn’t fully appreciate the film until I saw it years later on the silver screen. But even on first viewing, I grasped that this was a very different kind of science fiction movie — or movie of any kind — than any I’d seen before. It was a story told elliptically, with images rather than words, with important elements (like those damned aliens) completely unseen, existing only in negative space.

Soon after seeing the movie, I read Arthur C. Clarke’s novelization. Clarke was of course instrumental in the creation of the movie, which was inspired by his short story “The Sentinel.” Yet I found the book disappointing; it lacked the radical power of the film. And I realized that this was because the novel was (of course) told with words, which by their very nature make meaning explicit. In Kubrick’s film, as opposed to Clarke’s novel, the words are restricted to the dialog, which is mostly mundane and trivial. The movie’s meaning is implicit — which makes watching it both more difficult and more rewarding than reading the novel.

I don’t want to fault Clarke too much. He remains one of the great sf writers of the mid 20th Century, with Childhood’s End being a classic that has not faded with age. And it must be said that his 2001 is far better written than your average movie novelization. But his narrative by its very nature takes away the very thing that makes 2001 the classic that it is. It’s like the Cliff’s Notes for the movie. (And don’t get me started on 2010: The Year We Make Contact, in which Clarke felt it necessary to explain exactly why the computer HAL went on a rampage. Some mysteries are better left as mysteries. Did Leonardo need to tell us why the Mona Lisa was smiling?) If you haven’t seen the movie yet (and why haven’t you?) wait until after you’ve done so to read the novel. In fact, wait a few weeks, or months, and let the movie percolate through your mind for a while before you pick up the book.

I said before that 2001 has been an influential movie, and that is certainly true in so far as its design and visual effects. But really, I would argue that it hasn’t been influential enough. There have been very few movies since (certainly not mainstream ones) that have engaged their audiences with such a distinctive visual, non-verbal style. (Offhand, for American films, I can think of David Lynch’s Eraserhead and Terence Malick’s The Tree of Life. I may be the only person on Earth to have actually liked the latter. Or seen it, for that matter.) On the whole, 2001 was a giant step forward in the possibility of film, and it’s a pity that so few have followed up on it.

Looking over what I have written here, I realize I’ve said precious little about the movie itself. Perhaps that’s just as well. The movie resists any kind of pat summary (“Oh, it’s about the evolution of humankind, the danger of artificial intelligence, and the pleasures of eating a decent meal!”) and seems lessened by any attempts to describe it.

See the movie on as large a screen as possible. Allow yourself to fall into its slow and inexorable rhythm. If you don’t get it, or you find it pretentious twaddle, then watch it again. Notice the themes that cross the various segments of the movie: Food. Tools. Murder. Intelligence. Sleep. Growth. Wonder. Things that link all of humanity from primitive hominids to angelic star-children. For all the starkness of its scenes in deep space, the movie is rich with meaning and life.

And I dare you not to be moved when HAL sings “Daisy Bell.”