WARNING: This review contains spoilers for a 45-year old movie that you really should already have seen by now.

I was obsessed with Alien for years before I ever saw it.

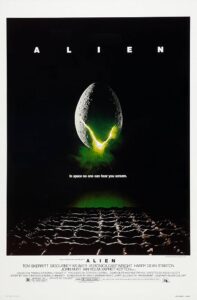

The film came out in the summer of 1979, the year I turned fourteen. I remember the remarkably effective ads on TV, featuring an unearthly egg, cratered like the moon (and looking nothing like the eggs seen in the movie, by  the way) starting to hatch, accompanied by that immortal tagline: In space no one can hear you scream. Woo! Cue the tingling of the spine.

the way) starting to hatch, accompanied by that immortal tagline: In space no one can hear you scream. Woo! Cue the tingling of the spine.

And then I read issues of Omni magazine that featured articles and photos from the movie, showcasing designer H.R. Giger’s viscid creations: the ancient spacecraft shaped like a malformed horseshoe, slick corridors that seemed like the inside of a shark’s intestines, and the glutinous podlike eggs. There were no images of the alien* itself, of course, to limit spoilers, but what I could see was enough to get me hooked. This vision of spaceship that seemed more organic than mechanical was a kind of science fiction far removed from “Star Trek” and Star Wars.

But of course I could not see it then. At that time, I only went to the movies if someone in the family took me, and none of them was irresponsible to take me to a hard-R-rated horror flick, revolutionary visuals or no. And I wasn’t ready to see it, really; I was a bit too susceptible to the effects of horror movies and television. When I was a few years younger, I would eagerly watch “The Night Stalker” on TV, and then have to spend the night in my parents’ bed because I was too terrified to be alone. Later, after watching John Carpenter’s Halloween, edited and sanitized for TV though it was, I could not sleep a wink afterwards. So, even at 14, I was self-aware enough to know that I was not yet mentally prepared to see whatever horrible things the alien did to people.

At least, not on celluloid. In the local bookstore, I found a comic adaptation of the movie (by comic legends Archie Goodwin and Walt Simonson, though their names were unfamiliar to me at the time), which I paged through with eager hands. Later, I borrowed the book of film’s novelization, by Alan Dean Foster (the king of SF movie novelizations in the late seventies and eighties; he must have written about thirty of them), which prissily omitted all the profanity but kept all the slime and blood. These were poor substitutes for the actual movie, to be sure, but they kept me turning the pages.

It was not until my college years that I finally saw the film itself and, miraculously, it did not disappoint. Naturally, by that point I knew the plot backwards and forwards, down to the order that the crew of the space freighter Nostromo get picked off by the alien, but for the first time I could appreciate Ridley’s Scott’s masterful direction, with the suspense slowly ratcheting up through the first half as the crew land on a forbidding planet, investigate the derelict spacecraft, and then begin nosing among those alien pods, before turning up the horror factor as the alien goes on its killing spree. The visual design is key, not just with the organic derelict craft, but also with the Nostromo itself, whose interiors range from claustrophobic corridors to sterile medical labs to vast storerooms, all of which come across as sinister and unsettling places.

Another element that I could only appreciate by seeing the movie was the quality of the cast. This must be one of the best ensemble of actors to appear together in a horror film: Tom Skerritt, John Hurt, Ian Holm, Yaphet Kotto, Harry Dean Stanton, Veronica Cartwright, along with a little-known actress named Sigourney Weaver.

Weaver’s Ripley, the film’s sole survivor (aside from Jones the cat) of the alien’s rampage, would become the character primarily associated with the Alien franchise — so much so that it’s hard to watch the movie and not see her as the heroine, whose survival is a foregone conclusion. However, she’s not actually played that way through most of the film. From the start, it’s Skerritt, playing the ship’s captain, who dominates the scenes and drives most of the action. Indeed, of all the cast, Ripley at first seems the most minor of characters. Certainly, Weaver was the least known of all the cast in 1979. In her early scenes, Ripley is officious and overly by-the-book, hardly what you’d call an action hero. But Alien is not an action movie.

In subsequent films of the franchise, Ripley is an action hero, most notably in James Cameron’s follow-up Aliens. There is much discussion in fan pages and movie review of which is better, Scott’s or Cameron’s movie, and more often than not (in the reviews I have seen) the consensus is that the latter is better, and the reason is often given that Cameron and Weaver made Ripley a true female action hero, a kick-ass woman armed to the teeth who could spit bullets and drop one-liners with the same panache as Stallone or Schwarzenegger.

I have to say that my own preference for Alien over Aliens is actually for pretty much the same reason. I find the flawed, everywomannish Ripley of the first movie far more interesting than the blaster-toting badass of the second. Not, I hasten to add, because I have any objection to having female action heroes, but because I generally find “ordinary” protagonists more interesting than superheroes. (I never really cared much for those Stallone and Schwarzenegger movies, either.) In the latter part of Alien, right up through the end, Ripley is half-insane with fear, muttering to herself hysterically as she sets the Nostromo’s self-destruct sequence and runs for the escape pod. There’s no grandstanding “Get away from her, you bitch!” moment, and this makes the climax far more terrifying, and more real, than that of Aliens.

I don’t want to give the impression that I disliked Cameron’s film; I think he did a great job of creating a sequel that respected the original but was not a simple retread. If it’s a bit more cartoonish in plot and characterization, it’s nonetheless engaging and entertaining. The same could not be said for any of the following sequels, Alien3 and Alien Resurrection. As for Scott’s 21st Century prequels, Prometheus and Alien Covenant, the less said the better. Not only are they filled with characters who make one stupid decision after another, but they provide answers to mysteries better left unsolved, with answers that are pretty stupid, as well.

Alien really works best if you ignore the excess baggage of the extended franchise and watch it as audience watched it in 1979: a simple and economical tale of a truly nasty boogeyman in a spacebound haunted house.

*Somewhere along the line, it became the norm in fandom to call the aliens “xenomorphs,” which I think is a ridiculous word, ugly in all the wrong ways. The term is never used at all in the first movie, so I will not do so here.